A Primer on Possible Worlds

July 9, 2016

Intro

The theory of possible worlds offers a conceptual framework for investigating the notion of possibility. It has motivated some wonderful discussions in the philosophy of science, mind, art, and literature, and even rears its head in contemporary fiction, film and TV quite often. I find the theory to offer a unique and sometimes useful cognitive toolkit, opening the door for some unusual (but interesting) questions, as well as providing a healthy bit of encouragement to remain open minded in the face of uncertainty.

In this post, I'll discuss a bit about the theory's core ideas, and point out a concrete way in which we can liken the methodologies of science and art using the theory. Thinking in terms of possible worlds also lets us ask some pretty fun questions - we'll discuss some of those too.

And please note: possible worlds is commonly studied through the formal symbolic system known as modal logic - I will not be covering much this, nor assuming any prior knowledge of it, but if you'd like to learn more, I encourage you to check out Introductory Modal Logic by Kenneth Konyndyk.

I also won't touch on the Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics here -- perhaps I'll write a follow up sometime in the near future.

Background

At a high level, the theory lets us reason about the way things could have been, or could be by introducting a concrete space of possibility: the space of possible worlds. So what's a world? Well, the term is not intended to be something like 'Earth' or any other planetary body. Instead, the term 'world' is more aligned with instantiations of the entire universe. It's more like the difference between the universe that the character's of Middle Earth occupy, and our universe: there are different rules, different inhabitants, and so on. Let's go with this definition:

For example, we could imagine a world called "One-Continent-World", in which the continents here on Earth never drifted apart. Intuition suggests that we can reason about such a version of reality. We can even ask questions: what other things might have changed? What would have happened from an evolutionary perspective? Would the dinosaurs have survived? Assuming humans still managed to evolve, how would our global infrastructure differ? There might be a sense in which these questions can be conceivably answered, as we are looking at a dramatically different timeline.

But these worlds don't just have semantic information at the level of our human-like experiences; we can also discuss details of a world's description like physical and mathematical laws. So, we might consider a possible world, Weird-Constant-World, in which many of our believed-physical constants are modified only slightly. What might such a world look like? It's hard to even imagine; more often than not investigations into possible world space will only make subtle perturbations to our own world so as not to jump too far, leaving us confused. It's hard to conceptualize a consistent version of reality that is so dissimilar from our own (even the One-Continent-World strains my imagination a bit).

Already in posing these questions we have addressed a fundamental intuition about our considerations of these worlds: we want them to make sense to us. When we alter one slight property, we go through the trouble of trying to figure out what else needs to change in order to accomodate such a world. It turns out this is actually related to a bizarre puzzle in how we digest the fictional worlds artists create, coined the Puzzle of Imaginative Resistance, from Hume's 1757 paper, and discussed more recently by Kendal Walton in 1990, along with some other folks.

So what good is all this? Why does thinking in this way buy us anything? To start, let's investigate how the basic methodology of science can be understood as a search through possible worlds

Science as a Search Through Possible Worlds

Consider the (totally massive) space of all possible worlds, visualized here as a big circle:

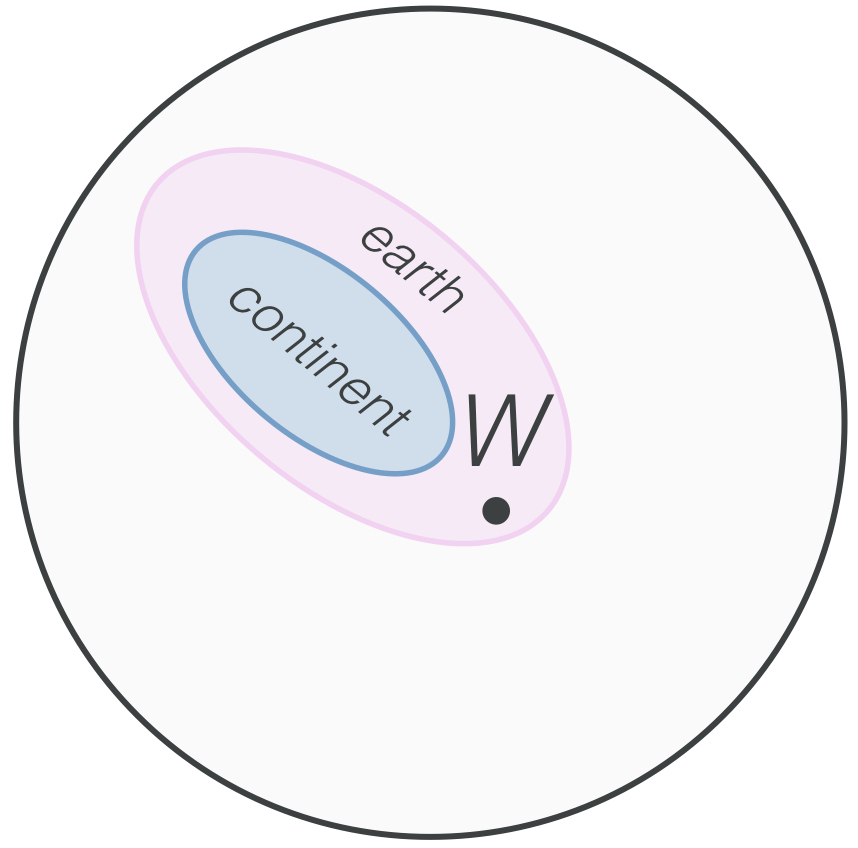

Any point in this circle is a unique little world. Well, somewhere in that big circle is us, too: a tiny point with a whole history (and future) of Mars, our Sun, Earth, and beyond; a description of fundamental physical laws, all past and future Pixar movies, and so on. Let's call the world we actually inhabit W, and let's put us on the map:

Now, one version of the scientific method (namely, the Hypothetico Deductive model) can be fleshed out as an algorithm that searches through the space of all possible worlds. The goal is to pin point our little world in that huge bubble, but, a priori, we're forced to deal with the searching through an infinite space of possible worlds. But! We have some tools available to us to help. Most importantly, we can ask questions, and divide the space up accordingly: are we in a world in which Earth revolves around the sun, or vice-versa? Are we in a world in which humans evolved on Earth? And so on.

This lets us divide the space of worlds based on whether a given property is true or false. Let's revisit our One-Continent-World again - consider the proposition "the planet humans evolved on, at present, only has one dominant body of land". Let's call this the set of continent worlds (worlds in which there is only one continent on Earth, forever and always). Now, let's consider the subset of possible worlds in which continent is True, shown below in the blue circle:

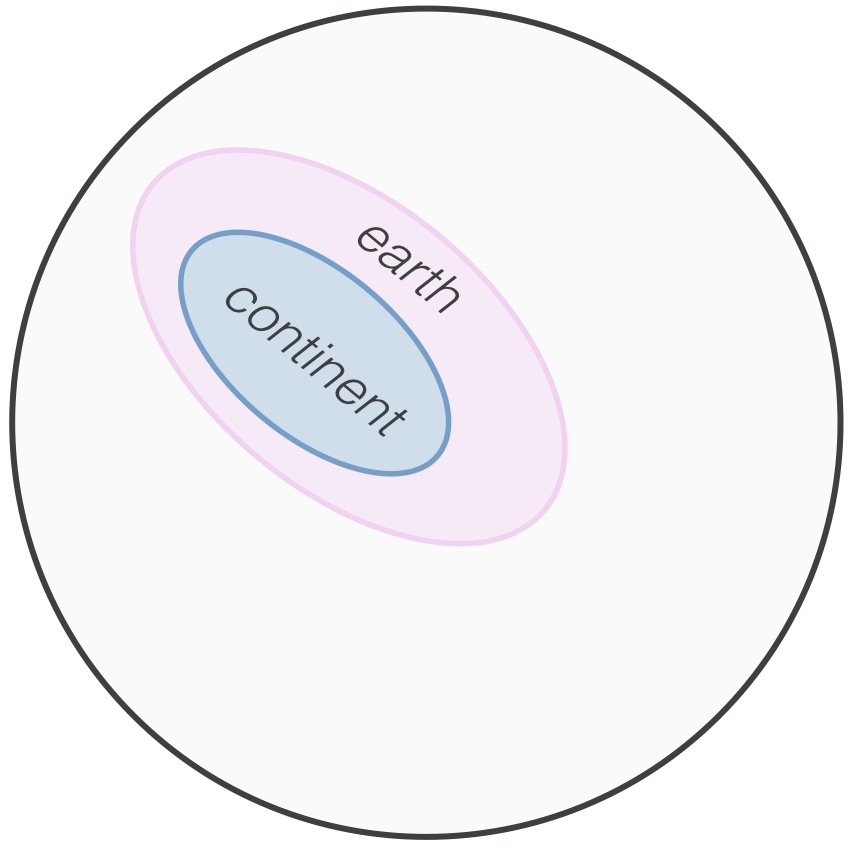

We can immediately reason about this collection of worlds. For instance, we know that any world in which continent is true, there must also exist an Earth upon which these continents exist! So, we can draw the set of possible worlds in which Earth exists, too, pictured in pink:

We can even start to reason about the relationship between these classes of worlds. Namely, every blue world is also a pink world. Right? What other qualities might have this relationship?

Now, how might we determine where our world lies in this space? Is it one in which there is one continent? Is it one in which there is an Earth? Given our current knowledge, we can actually place ourselves in this picture: in the pink, but not in the blue! (There is the detail of time - that at some point in the past, we had one continent, let's set considerations of this kind aside for now). We'd be here:

Somewhere, floating in that pink blob is our world. But of course, there are far too many other worlds for us to know for sure which one is us. Science, or at least, the Hypothetico Deductive model of science, is about hypothesizing a collection of worlds we belong to, and then either rejecting or verifying that hypothesis: shifting our place in or outside the bubble, honing our understanding of where our world lies in this space.

Naturally, there are some things we can never verify, or falsify. There are some propositions we will just never figure out (tough luck!). So, we are fundamentally incapable of pinpointing exactly which world we're in, but, hopefully, we can narrow our search pretty far! According to this particalr model, science is about repeatedly posing questions about our world being in a certain colored bubble, or not in a certain colored bubble, then going out in the world, making fine tuned observations, and determining where our world is likely to lie in the space. It's about searching through this massive space to isolate our world.

This brings up an important debate in the history of the philosophy of science: the role of verification and falsification. Verification was originally pitched by a group of Philosophers called the Logical Positivists that believed all the knowledge of science should be built up through verification. Under this principle, science is about claiming that our world is in a specific bubble (say the pink one), and then going out in the world and observing things that support our membership to the pink-club. The Logical Positivists also want to say that claims that are not verifiable aren't worth investigating, since they ultimately don't serve in our understanding of what world we're in.

On the flip side, the principle of falsibility (introduced by Karl Popper) stipulates that science is about falsifying claims about our world. That is, showing that our world does not lie in some other bubble: for instance, that we're not members of the blue-club. Under this notion claims that are not falsifiable are also not worth investigating, since we can never determine whether our world has that property or not. In some sense this paints a picture about the limitations of inquiry: there are certain claims about our world that we'll never figure out.

Takeaway: Science can be (imperfectly) cast as a search through the infinite space of possible worlds in search of our own (or at least our neighborhood). Further, we'll never be able to determine precisely which world is ours, but we can increasingly hone our understanding of our rough territory.

Art as a Search Through Possible Worlds

To me, art often performs a similar search.

Art, in many mediums, allows us to inspect other worlds, often closely related to our own. They allow us to peer into alternate time lines in which critical events didn't take place in human history, or look into future worlds in which technological development diverged slightly from our own. We can peer through the frame of a painting or the pages of a novel into a world with wildly different rules than ours and come away wondering about our own world.

There is perhaps no unifying agenda with art, though I tend to believe that a thorough investigation of other worlds through artistic mediums can improve our understanding of our experience in this world. We can often export truths from these other worlds: for instance, if being a jerk to squirrels is bad in the world of Harry Potter, it may be the case that being a jerk to squirrels is bad in our world, too.

To summarize: the method of science and art can be viewed as sharing a core piece of methodology: the former, of reaching out into possible world space to find our world, and the latter, of observing other possible worlds as a means of learning more about our own personal experiences in our world. There isn't a grand truth to all this, I just find it interesting! (and hope you do too)

Reasoning from Possibility

A nice aspect of the theory is that it situates arguments in a place of open mindedness. Suppose you are discussing a contentious issue like religion or free will with a good friend. Your friend happens to make a claim you disagree with. Instead of jumping straight for a well-thought-out counterargument, you can position yourself from the perspective of a possible world in which your friend's claim is true: what might such a world look like? Is it possible that this new world is our own world? If not, why not? If so, why? We can briefly try on the shoes of someone who believes this claim to be true, and just see if it feels possible. I tend to find such an exercise to be charitable, and a good epistemic practice.

As mentioned at the beginning, there is an entire formal language to possibility (modal logic) that deals with relationships of necessity and possibility. This language and its associated inference rules are quite fascinating, and deserve quite a bit more than one paragraph. Modal logic gives us intuitive ways to make statements about the relationship between the necessary and the possible. A nice feature is that the vast majority of claims are at least possible - it is more difficult to prove a claims impossibility than to prove its possibility! (Perhaps another reason to stay open-minded?)

Some Questions

First: are there propositions that are true in all possible worlds? These are the so called necessary claims. But what might they be? For instance, one might stipulate that if some form of god or gods were to exist, presumably it/she/he/they would exist in all possible worlds. Additionally, many feel pulled to claim that mathematical truths are necessary truths. There is certainly some intuition to this: when we spoke about properties that might change in different worlds, such as the continent property, we can at least conceive of what it would mean for such a property to be true or false. But we can't even grasp what it means for certain mathematical truths to be false. How could a world exist in which contradictions exist? The inherent consistency we seek out when we inspect possible worlds (particularly through fiction) is perhaps what enables us to export concepts from these worlds back onto our own - we assume that these concepts generalize. Naturally, if mathematical truths are true in all possible worlds, then learning about them in one world will let us export them to ours. The same goes for other types of necessary truths, too (like the squirrel-jerk example).

Second: are these worlds purely human constructs, or do they actually exist? This question is closely in line with the many worlds interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Some, like one of the original thinkers on possible worlds, David Lewis, claim that every single possible world actually has associated with it a physical reality, filled with planets and people and penguins.

Third: what are the epistemic relations between possibility and necessity? If a claim is necessary, is there any means by which we can come to this knowledge? Can we justify it in a satisfactory way? Again, many folks want to jump to mathematical claims being necessary claims, but what does an argument for their necessity look like? What would a convincing argument for a claim's necessity look like?

Fourth: what is the relationship between possibility and probability? The formal system of probability has enjoyed wild success, both theoretically and in wide range of applications. There are intimate connections between the two theories. Probability in many senses hones the Hypothetico-Deductive model mentioned above by assigning degrees of belief to different propositions in place of categorizing claims as true or false. As you likely expect, there's a lot more to that story.

Thanks for reading - let me know if you have any follow up questions, or find any typos :)

Cheers!

-Dave